how to illustrate a story

The three-act structure is perhaps the most common technique in the English-speaking world for plotting stories — widely used by screenwriters and novelists. It digs deep into the popular notion that a story must have a beginning, middle, and end, and goes even further, defining specific plot events that must take place at each stage.

In this post, we dissect the three acts and each of their plot points — using three-act structure examples from popular culture to illustrate each point.

Let's begin! In three, two, one...

What is the three-act structure?

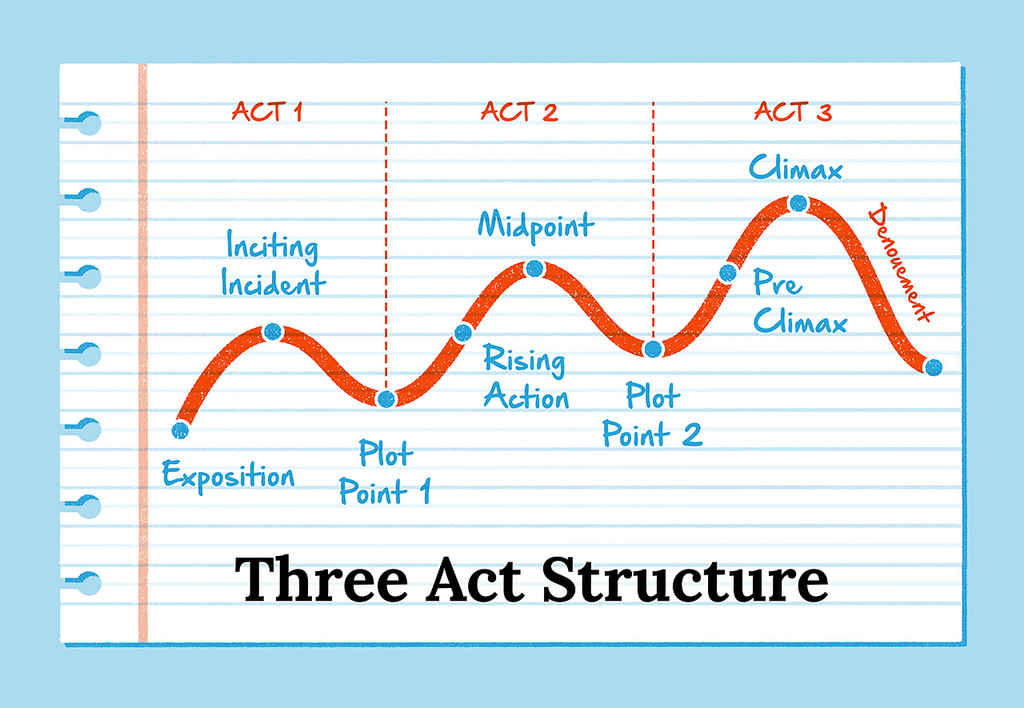

The traditional three-act structure includes the following parts:

- Act I - Setup: Exposition, Inciting Incident, Plot Point One

- Act II - Confrontation: Rising Action, Midpoint, Plot Point Two

- Act III - Resolution: Pre Climax, Climax, Denouement

Within each Act is a number of different "beats" — a plot event. According to Aristotle, who first analyzed storytelling through three parts, each act should be bridged by a beat that sends the narrative in a different direction. In Poetics, he posits that stories must be a chain of cause-and-effect beats: each scene must lead into what happens next and not be a standalone "episode."

Now that we know what the three-act structure is, let's dive into how it works.

PRO-TIP: Have you ever wondered how long your novel should be? Take our short quiz below to find out!

✅

How long should your book be?

Find out what word count the industry expects for your genre — it takes 15 seconds!

How to use the three-act structure

It's clear that a lot of writers agree that "good things come in threes" when it comes to storytelling. In this section, we'll dig deeper, breaking each act into three further "beats." And just so we're not talking in purely abstract terms, we'll be using The Wizard of Oz and The Hungers Games as examples throughout (and we've also got a post with a more in-depth analysis of trilogy structures).

Free course: Mastering the 3-Act Structure

Learn the essential elements of story structure with this online course. Get started now.

Act One: The Setup

Despite being one of three sections in a plot, Act One typically lasts for the first quarter of the story.

Exposition

Act One is all about setting the stage: readers should get an idea of who your protagonist is, what their everyday life is like, and what's important to them. Of course, nobody's life is perfect, and the exposition should give readers a sense of the current challenges facing the main character. Their desire to overcome these challenges will inform their overarching character goal.

Plotting your exposition will require you to already have a fairly firm grasp on your character. Prepare yourself with these resources:

- How to Develop Characters Your Readers Won't Forget

- 8 Character Development Exercises to Help You Nail Your Character

- How to Create a Character Profile: the Ultimate Guide (with Template)

Examples

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy's home life in Kansas forms the bulk of the exposition. We see that her family are hard-working farmers and that she has a dog she cares for called Toto. We learn that Dorothy feels misunderstood and under-appreciated.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss is introduced as a responsible, determined teenager who hunts illegally to feed her family, which suffers under the rule of the Capitol.

Inciting Incident

This is the catalyst that sets the protagonist's adventure in motion. The inciting incident is a crucial beat in the three-act story structure: without it, the story in question wouldn't exist. The inciting incident proposes a journey to the protagonist — one that could help them change their situation and achieve their goal.

Author and editor Kristen Kieffer suggests asking yourself the following questions to help you craft the inciting incident:

- How is my protagonist dissatisfied with their life?

- What would it take for my protagonist to find satisfaction? (This is their goal).

- What are my protagonist's biggest fears and character flaws?

- How would the actions that my protagonist needs to take to find satisfaction force them to confront their fears and/or flaws?

The catalyst is referred to as the "call to adventure," and asks your protagonist to push themselves out of their comfort zone. Does it make sense for your character to resist action after the inciting incident? If so, you may want to dedicate a scene (or sequence of scenes) between the plot points — in particular, Inciting Incident and Plot Point One — for your character to reflect on their motivations: how will their life change? How will their journey affect the lives of those around them? What's at stake if they're successful? What's at stake if they fail? Depending on the character, and their core fears and flaws, you may need to raise the stakes so that the character has no choice but to accept.

Examples

Dorothy runs away from home when she feels like her family doesn't take her concern over Mrs. Gulch's dislike for Toto seriously. She encounters a Professor who encourages her to return home, where a twister causes Dorothy to be struck in the head by a window. When she wakes up, she's in The Land of Oz.

Katniss' beloved younger sister, Prim, is randomly chosen to participate in a televised fight to the death.

PRO-TIP: Did you know that the three-act structure is just one of many story structures that you can use? You can read more about the Hero's Journey and Dan Harmon's Story Circle here — or head here to find three additional models.

Plot Point One

It's full speed ahead now! No more hemming and hawing for your character: the First Plot Point represents the protagonist's decision to engage with whatever action the inciting incident has sent their way.

In some novels, the Inciting Incident and Plot Point One happen in the same scene. For instance, in The Hunger Games, Prim's selection as a tribute is the catalyst. Immediately after, Katniss volunteers herself in her sister's place, representing her reluctant acceptance of the call to adventure.

Think of the First Plot Point as the springboard that launches your character into Act Two. Speaking of which…

Examples

Frightened and confused, Dorothy wants to go home and is told by Glinda the Good Witch that the only way is to follow the Yellow Brick Road to the Emerald City where The Wizard lives. Dorothy decides to follow the Road, and it's established the Wicked Witch will try to stop Dorothy on her journey.

Katniss volunteers to take her sister's place in the Games — thus pulling her into the heart of the story.

Act Two: Confrontation

Typically the longest of all three sections: Act Two usually comprises the second and third quarters of the story.

Rising Action

Here's the part where Dorothy waltzes down the Yellow Brick Road to meet Oz who sends her home without a hitch, right?

Nope. This is the part where the protagonist's journey — or the pursuit of their goal — begins to take form and where they also first encounter roadblocks. The protagonist gets to know their new surroundings and starts to understand the challenges that lay before them. This is the part of the story where you should better acquaint readers with the rest of the cast (both friends and foes) and the primary antagonist. You will also elaborate on the story's overarching conflict (whether it's a person or a thing).

As the protagonist starts to learn more about the road ahead, they'll change and adapt in order to have a better chance of achieving their goal. In this way, the main character is usually more reactionary than proactive in the Rising Action phase.

Examples

Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and Lion. They travel down the Yellow Brick Road, where they encounter obstacles such as apple-throwing trees and sleep-inducing poppies.

Katniss trains to survive the Games. After the Games start, she gathers supplies and runs for her life. Thereupon, she faces many physical dangers before a fearsome group of Tributes discovers and begins to hunt her.

Midpoint

It's no big surprise that the Midpoint takes place at… drumroll, please… the middle of the story! A significant event should take place here, usually involving something going horribly wrong.

Return to the protagonist's main goal to establish what this Midpoint event should be. What would have to happen for them to feel that their goal is being directly threatened? What could make the character even more acutely aware of the stakes at hand?

Examples

Dorothy finally reaches the Emerald City and meets with The Wizard — who turns out to be a big disappointment. He initially refuses to meet with them, and when he eventually does, he declines to help them until they bring him the Wicked Witch's broomstick.

Katniss — having been hunted and trapped by her fellow Tributes — has to take violent action to escape their clutches. This is the event that convinces her to stop running and start fighting to win the Games.

Free Download: Three-Act Structure Template

Effortlessly plot your story with our customizable template. Enter your email and we'll send it to you right away.

Plot Point Two

Our poor protagonist has fallen on hard times. They thought they were making headway on their goal and then the Midpoint came and threw them off their rhythm.

Give them some time to reflect on the story's conflict here. The aftermath of the Midpoint crisis will force the protagonist to pivot from being a "passenger" to a more proactive force to be reckoned with. You might want to plan a sequence here in which the main character's resolve is bolstered through productive progress on their journey's goal. Think of Plot Point Two as the pep talk your character needs in order to stand up straight and get ready to meet their antagonist head on. They'll need this confidence to handle what comes next…

Examples

Dorothy must decide whether to take the risk of heading to the Wicked Witch's castle or to give up on her chance of going home. She and her companions decide to confront the witch.

Katniss works to destroy the Tribute's supply cache and kills a Tribute in an effort to protect Rue. She later tracks down Peeta, fights another Tribute for medicine that will heal his injured leg, and makes sacrifices to keep them both alive.

Act Three: Resolution

The final act typically takes up a quarter of the story — sometimes less.

Pre-Climax

Even the strongest knight has weak spots in their armor: their deep-rooted fears and flaws. As the protagonist has been gearing up to meet the antagonist head-on, their main foe has also been getting stronger and is now ready for battle.

Also called "The Dark Night of the Soul," Act Three starts with the final clash between the protagonist and the antagonist. We've experienced the entire journey with the main character — but this is where we get our first glimpse of the antagonist's true strength, and it usually catches the main character off guard. Even though most readers are aware that the protagonist typically wins the day, we should have some doubt here about how the last act will play out, and if the main character will be okay.

Examples

While on the way to the Wicked Witch's castle, Dorothy is captured. The Witch finds out that the ruby slippers can't be taken against Dorothy's will while she's alive, so she sets an hourglass and threatens that Dorothy will die when it runs out.

Katniss realizes that the mutated hounds chasing her bear striking resemblances to deceased Tributes, including those she killed, dredging up trauma Katniss had suppressed to survive.

Climax

The climax signifies the final moments of the story's overarching conflict. Since the antagonist has just hit the protagonist where it hurts in the previous beat, the protagonist has to lick their wounds. Then they face-off one more time and the main character lays the conflict to rest.

The climax itself is normally contained to a single scene, while the pre-climax typically lasts longer and might stretch over a sequence of events.

Examples

Dorothy throws a bucket of water on the Scarecrow who is on fire. She ends up accidentally dousing the Witch who melts into a puddle. The guards hand the Witch's broom to Dorothy.

Katniss saves Peeta from Cato, the final tribute whom she later kills as an act of mercy when he is mauled by mutts. When the Gamemakers try to force Katniss and Peeta to fight to the death, they move to commit suicide instead, maintaining their integrity despite the Capitol's demands.

Denouement

Finally, the dust settles. If the protagonist's goal is not immediately obtained during the Climax, the denouement is where this should be achieved (or redefined, if their goal changed during Act Three). Along with this, the denouement should also:

- Fulfill any promises made to the reader. Check out our post on Chekhov's Gun to learn more about this,

- Tie up significant loose ends,

- Underscore the theme, and

- Release the tension built up during the climactic sequences of events.

If you want to learn more about nailing your story's resolution, check out our post on how to end a story.

Examples

The Scarecrow receives a diploma, the Tin Man receives a "heart," and the Lion receives a medal of valor. The Good Witch explains that Dorothy has always had the power to go home; she just didn't tell her earlier because she wouldn't have believed it. Dorothy taps her ruby slippers and heads back to Kansas to lovingly greet her family.

The Gamemakers cut the game short after realizing Katniss and Peeta's intent to commit suicide. They are taken to the hospital and later home, where they must put on a show as the winners of the Games, but are ultimately safe — for now.

The three-act structure is just one way to think about a story, so writers shouldn't feel limited. The benefit of using the three-act structure is that it will help ensure that every scene starts and end with a clear purpose and direction. Even if you don't start outlining your novel with it, if you find yourself struck by pacing issues, it's often useful to fit your story into the three-act structure to see why that might be.

how to illustrate a story

Source: https://blog.reedsy.com/guide/story-structure/three-act-structure/

Posted by: reidgropen.blogspot.com

0 Response to "how to illustrate a story"

Post a Comment